Robert Carr Roberts (1858-1951)

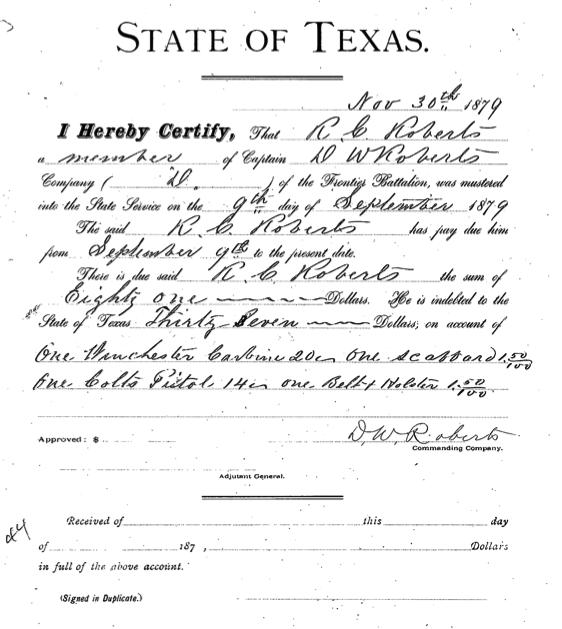

R. C. Roberts Musters into State Service (Texas State Library & Archives)

When he was twenty-one years old, R. C. Roberts of Fredericksburg became a regular Texas Ranger serving for fifteen months in Company "D," Frontier Battalion, of which his half-brother, Dan Roberts, was Captain. He was not inexperienced in frontier service when he joined the Ranger company, for with his family frontier service was almost a heritage. His father, Alexander Roberts, came to Texas in 1836 to help fight the battles of the Texas Revolution, and the family followed up the Texas frontier, helping pave the way for other settlers. Their frontier experiences would fill volumes.

Bob Roberts was born on October 1, 1858 in Llano county near Packsaddle Mountain. There were scarcely any settlers in that part of the country, and during the Civil War the Indians were so troublesome that the Roberts family moved to Lockhart. While Bob Roberts was still a child they moved into the Round Mountain community of Blanco County. Indians were still making raids into the community to steal horses, and the Roberts boys learned to be ever alert and watchful for them. Even as a boy, he carried a gun to school with him.

Once, when he, in company with his older half brother, Alex, who was then about fifteen, a neighbor, and a negro had gone fishing to the Pedernales, they saw some Indians, travelling along single file. There were about twenty one Indians, all afoot, except one, who rode an old nag. The boys were upon a little hill, when they discovered the Indians, and felt comparatively safe, for they were certain that the Indians would not climb the hill to reach them. The boys had come on this trip poorly armed, and they were not eager to meet the Indians, who stopped in their marching as soon as they discovered the presence of the boys. They stayed perfectly still, watching the boys until they saw the boys move on.

The boys hurried to their home, which was eight miles away, gave the alarm, and when a crowd of men had been gathered, returned with them to the spot at which they had seen the Indians. There was much discussion over the direction which the Indian had taken, and so the trail was lost. Later it was learned that the Indians had crossed the Pedernales at the falls, to which the boys had intended to go fishing. And somewhere along their trail the Indians met an old man, Mr. Moore, whom they murdered. Other people of the community were murdered by the Indians within a short time, Mr. and Mrs. Thomas Phelps and Jim Dollahite. The life of the settlers had become so uncertain that out of self defense the young men of the community pledged themselves to follow the next band of marauding Indians and bring them into battle. Their decision brought about the battle of Deer Creek, one of the last Indian fights to be fought in that section of the country.

Driving along the highway from Austin to Johnson City one passes through a gap between the hills, about two miles from Johnson City and about fifty miles from Austin, where nearly sixty years ago a battle was fought between a posse of ten men from near the settlement of Round Mountain and over three times that number of Indians.

[The Battle of Deer Creek, August 1873]

Two of the brothers of Bob Roberts took part in this battle, and were wounded there, but Bob Roberts, who was at the time thirteen years old did not get to go along. When news reached the Roberts home one day in August of 1873 that Indians were in that vicinity, the two eldest Roberts boys remembering their pledge, quickly saddled their horses. They told their younger brother Bob, that he might go along if he could find a saddle horse. But there was no other saddle horse near the house, and his brothers were in a hurry to be off. To this day Bob Roberts has not forgotten how eager he was to go with them, and how keenly disappointed he was at being left behind.

Captain Dan Roberts in his book, Rangers and Sovreignty [San Antonio, Texas: Wood Printing, 1914] gives an account of this battle in which the handful of men of the Round Mountain community battled with a band of Indians. When the white men were a short distance away, an Indian, placed upon guard on a hill, saw the white men approaching, and ran to give warning to the others. Thus the Indians were able to entrench themselves and the horses safely in a ravine below the hill, while the white men must approach in the open. George Roberts was wounded throught the nose, and Dan Roberts through the thigh. Seeing, after a while that they could not possibly overpower the Indians, the posse of men ceased firing. As soon as the firing ceased, the Indians retreated. As he was leaving Dan Roberts saw two old Indians climbing up the side the mountain, and he called to them in Spanish:

"Bring your men out into the open and let them fight."

To which the old Indian retorted:

"Take your men out and let them go to hell."

The two wounded Roberts boys were brought to a nearby ranch, and other men took up the trail of the Indians never, however, coming upon the Indians. They found evidence along the trail that wounded Indians had been carried along, and they came upon several graves.

On the day after the battle Bob Roberts went with others to view the battle ground, to which he had almost accompanied his older brothers the day before. He saw the trampled brush, disturbed by the right [sic], found a horse that had been killed, one belonging to an Indian. Farther along he saw the spot where the Indians had made their camp fire to prepare dinner a short time before the fight, not far from the ravine where the Indians had sheltered themselves.

Probably as a result of his valour in this fight Dan Roberts was commissioned a year later, as a charter member of Company "D," of which he later became captain.

[Joins Rangers]

When in 1879 Bob Roberts joined the rangers, the company was stationed in Kimble county on Bear Creek, a branch of the Llano, four miles from Junction City. Kimble County at that time was the hangout of dangerous outlaws, who had been driven out of nearby counties, and who took refuge in the hills and caves of less settled country. On his first night in ranger camp, several wild, desperate looking outlaws were brought in. Bob Roberts recalls that these men, shackled, were placed in a tent, and he a "green horn," was placed on guard. He says that there was no need to warn him that he must not go to sleep, for he had no thought of sleep, while he had these men in the tent to guard.

Bob Roberts was with the rangers in Kimble county for only two months, when his father's health became so uncertain that he was called home. When, later, he rejoined the rangers, they were stationed at Fort McKavett. From here the rangers were sent as scouts all over the state. Probably the longest scout in which Bob Roberts joined, lasted more than sixty days, and took the rangers from the head of the Llano to New Mexico.

[Scouting Horse Thieves to New Mexico]

A ranchman from the head of the North Llano hurried into the ranger camp one day to report that all of his horses, and a number of horses belonging to neighbors had been stolen. Captain Dan Roberts at once detailed seven men to take up the trail of the horse thieves, instructing the rangers to catch the thieves, anywhere they could. Bob Roberts remembers that he and the other rangers, in charge of Corporal Kimble, left on horseback, with a pack mule to carry their supplies. That was about the tenth of September, 1880.

For the first two days the rangers had no trouble in following the trail, which led for sixty miles over the dry divide, striking Beaver Lake, the head water of the Devil's River. But heavy rains came and the trail was washed out. The rangers were certain that the men with the horses were striving to reach New Mexico, and so they followed in that direction. For several days they traveled without any information concerning the horse thieves, or assurance that they were making headway At Howard's Well they found some U. S. soldiers encamped, and the rangers spent the night there, helping do picket duty on watch for Indians. The soldiers had sighted Indians the day before, and were on the watch for them.

Since the country west of Howard's Well was frequented by Indians during this time, and the rangers were working in conjunction with the U. S. government to protect the frontier against the Indians, Corporal Kimble gave the rangers strict orders to keep a watch for Indians as they proceeded farther west.

Only a short time before the Indians had attacked a stage coach on the divide between the North Fork of the Concho and the Pecos. The Indians had murdered the stage coach driver, and the escort of negro soldiers.

When, late one evening, the rangers reached Fort Lancaster, near the Pecos River, they were informed that only the day before men with a bunch of horses, answering their description had passed that way. The rangers traveled all night. By the time they had reached Horse Head crossing on the Pecos most of their horses were worn out, but the rangers procured fresh horses, and rode on in pursuit, until they were near the state line of New Mexico, where they overtook the horse thieves.

They discovered the men to be half breeds, Jim and John Potter. When the rangers demanded their surrender, a fight ensued, in which both Jim and John Potter were wounded. And then a strange thing happened The firing was heard at a near by cattle ranch, and one of the ranch hands came running to investigate. It was Frank Potter, the brother of Jim and John Potter, an honest, reliable cowboy. For a long time he had known nothing of the where-abouts of his two brothers, and he was distressed to discover that they had been the cause of the firing and that one of them was mortally wounded. Jim Potter died shortly after the battle. He was burled on the prairie near the battle ground. Because the rangers did not have the proper tools to dig with, it was only a shallow grave. At night wolves came to scratch and howl over it.

John Potter was so severely wounded that the rangers stayed in camp with him for nine days, before taking him to Fort Davis. He was kept there until he was able to be brought back to Fort McKavett, the company's headquarters in Menard County. When they made camp on the first night, Potter attempted to escape. When he was taken from the hack which the rangers had secured to take him back, he jumped up and began to run. But before he was fifty feet away, he was overcome by weakness and fell.

It was now the middle of November. Winter had set in and it was bitterly cold. The rangers made their way back through snow and sleet. They had recovered only five of the stolen horses, and several died on the way back. They were able to deliver only two of the stolen horses to their owner in Kimble county. Their owner, probably thinking that the rangers had only done their duty, received these horses back without a word of thanks.

Potter was placed in a San Antonio jail for safe keeping, until district court should convene in Kimble county. Then the Kimble county sheriff went to get Potter, but Potter never reached Kimble county. Near the Guadalupe River a mob over powered the sheriff and shot Potter.

[Willow City and Fredericksburg]

After he had been with the rangers for about fifteen months Bob Roberts desired to resign from Ranger service, and in 1881 was granted honorable discharge. The Roberts family had moved to Willow City, when there were only a few people in that community, sometime during 1876. A few years later the Harrison family moved into the Willow community.

Lattie Frances Harrison Roberts (1865-1953)

Bob Roberts was married to Miss [Lattie Frances] Harrison on January 11, 1887, and until six years ago [1928], when they moved to Fredericksburg, Mr. and Mrs. Bob Roberts made their home at Willow City. They have three children, M. H. Roberts of San Antonio, Mrs. Mary Colmyer of California, and Mrs. Zula McCullar of San Antonio.

Rangers of the frontier who did Indian scout duty, are supposed to receive pension. But someone in authority seems to doubt that Bob Roberts did Indian scout duty, and so he never received the pension he so well deserves, and which most of the members of his company received.

Bob Roberts, old time fiddler, cowman and ranger, is now seventy-five years old. He and Mrs. Roberts live in the comfortable little home in town where they have room for a garden and a stable for the horses. Mr. Roberts still feels most at home on his horse and he manages to spend a large part of his time on horseback. Although his life, as that of all of the Roberts family has been rich with pioneer experiences, he does not boast of them. He is reserved and careful to be exact in relating any of his experiences, rather inclined to undervalue them . His quiet humor never fails him in whatever he discusses.

With his characteristic humor he sums up his experience after he left ranger service:

"After I was married I farmed for 10 years. I thought I had the prettiest wife and sweetest babies, and wore the biggest patches on my pants of almost any man in Gillespie County. But from 4 to 7 cent per pound for cotton didn't appeal to me. So I went into the cattle business, and followed that for twenty years. Then came the drought in 1917 and '18, and put me out of business, and I am just staying put. Some days we have much on the table, most of the time it is much - but - much less!"